自闭症

|

|

Consideration of psychiatric disorders, especially autism, can vary by nation due to cultural differences in diagnosis and interpretation. Autism is four times more prevalent in boys than girls and knows no racial, ethnic, or social boundaries. Family income, lifestyle, and educational levels do not affect the chance of autism's occurrence.

In western countries : 100 per 10,000 (Baird et al., 2006; Baron-Cohen et al., 2009; Elsabbagh et al., 2012) In Hong Kong: 16.1 per 10,000 (Wong & Hui, 2008) Most recent data from CDC in the US: 147 per 10,000 (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014) In China: A pilot study suggests that autism is currently under-diagnosed in China,which might be similar to Western estimates (Sun et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2013). In this regard, a national prevalence study is undergoing at the moment. http://www.cam.ac.uk/news/autism-prevalence-in-china-0

SOME OBSERVATIONS OF AUTISM Genetic Factors that Increase the Risk of Autism Although there is a strong genetic component to autism, no specific genes for autism have yet been found. One or more autism-linked abnormalities have been found on virtually every chromosome, with some chromosomes being implicated more frequently. (Allen, Vessey, Schapiro. (2010). Primary Care of the Child with a Chronic Condition, Fifth Edition. St. Louis Missouri: Mosby). Researchers from The Scripps Research Institute reported in the journal Cell, November 2012, that they are discovering how genetic mutations can be responsible for the behavioral and cognitive problems found in people with autism. Environmental Factors that May Increase the Risk of Autism Researchers from the University of Aarhus, Denmark reported in the journal Pediatrics (November 12, 2012) that if a pregnant woman gets the flu or has a fever that persists for more than one week, there is a greater chance that her child will be diagnosed with autism by the age of three.

Head researcher, Hjordis Osk Atladottir, emphasized, however, that 98% of those who did become ill in their study went on to give birth to healthy babies who never developed autism. Recent research regarding autism risk has focused on parents with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, older fathers, immune system irregularities, and air traffic pollution during pregnancy.

Behavioral Characteristics of Autism According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the hallmark feature of autism is impaired social interaction. Children may fail to respond to their name, and often avoid eye contact with other people They have difficulty interpreting what others are thinking or feeling because they can't understand social cues, such as tone of voice or facial expression, and they don't watch other people's faces for clues about appropriate behavior. They may appear to lack empathy.

Many children with autism engage in repetitive behaviors such as rocking or twirling, or in self-abusive behavior such as biting or head-banging. Self-injurious behaviors may occur in unfamiliar, overwhelming, or frustrating situations. They don't know how to play interactively with other children. Some speak in a sing-song voice about a narrow range of favorite topics, with little regard for the interests of the person to whom they are speaking.

Some experience significant language delays; however, with therapy most people with autism do learn to use spoken language, or learn to communicate. Many nonverbal or nearly nonverbal children and adults learn to use communication systems such as pictures, sign language, electronic word processors, or speech-generating devices.

Common repetitive behaviors include hand-flapping, jumping and twirling, arranging and rearranging objects, and repeating sounds, words, or phrases. Many children and adults demand extreme consistency in their environment and daily routine; slight changes can be very stressful and lead to outbursts.

Many individuals with autism have difficulty processing and integrating sensory information such as sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and/or movement. They may perceive seemingly ordinary stimuli as painful, unpleasant or confusing. Some with autism are hypersensitive to sounds or touch; others are under-responsive. Some with autism eat non-food items such as dirt, clay, chalk, or paint chips.

INTRODUCING SOME TEACHING PROGRAMS While children and adults with autism benefit from interventions that can reduce symptoms and increase skills and abilities, identifying and verifying the effectiveness of treatments or interventions will save families time and energy looking for the best way to help their children. A comprehensive treatment plan would include both education and behavior management, and often pharmacologic treatment. It is suggested that parents try only one new treatment at a time so that any changes observed can be ascribed to that treatment. An overview and analysis of available interventions has been provided, as well as an evaluation of their use for individuals with autism-related disabilities, in an effort to identify scientifically validated methods. (Richard Simpson, et al, (2005). Autism Spectrum Disorders: Interventions and Treatments for Children and Youth. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press). A useful rating for interventions and treatments is provided, identifying: Scientifically Based Practices: those that have significant and convincing empirical efficacy and support Promising Practices: those that appear to have efficacy and utility, even though the intervention requires additional scientific support to be considered a scientifically based method Limited Supporting Information for Practice: those interventions and treatments for which there is little or no scientific evidence. If an intervention or treatment is judged as lacking support, it is not an indication that it is necessarily without merit; rather, that evidence is lacking to make an objective, scientific judgment. Not Recommended: interventions and treatments that have been shown to lack efficacy and that may have the potential to do harm.

A summary of the ratings is provided below: Scientifically Based Practices: Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) Discrete Trial Teaching (DTT) Pivotal Response Training (PRT) Learning Experiences: An Alternative Program for Preschoolers and Parents (LEAP) Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) Joint Attention Symbolic Play Engagement Regulation (JASPER)

Promising Practices Play-Oriented Strategies Assistive Technology Augmentative Alternative Communication (AAC) Incidental Teaching Joint Action Routines (JARS) Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) Structured Teaching (TEACCH) Cognitive Behavioral Modification Cognitive Learning Strategies Social Decision-Making Strategies Social Stories Pharmacology Sensory Integration (SI)

Limited Supporting Information for Practice Gentle Teaching Option Method (Son-Rise Program) Floor Time Pet/Animal Therapy Relationship Development Intervention (RDI) Fast ForWord van Dijk Curricular Approach Cartooning Cognitive Scripts Power Cards Auditory Integration Training (AIT) Mega-vitamin Therapy Scotopic Sensitivity Syndrome (SSS): Irlen Lenses Art Therapy Candida: Autism Connection Feingold Diet, Herb, Mineral, and Other Supplements Gluten-Casein Intolerance Mercury: Vaccinations and Autism Music Therapy

Not Recommended Holding Therapy Facilitated Communication (FC)

Description of the practices themselves is available elsewhere; however, the ratings provided by this reference may prove useful to parents and professionals as they consider best practice methods for effective programming.

References

Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Meldrum, D. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet, 368(9531), 210-215. Baron-Cohen, S., Scott, F. J., Allison, C., Williams, J., Bolton, P., Matthews, F. E. (2009). Prevalence of autism-spectrum conditions: UK school-based population study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(6), 500-509. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ, 63 Suppl 2, 1-21. Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y. J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcin, C. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res, 5(3), 160-179. Sun, X., Allison, C., Matthews, F., Zhang, Z., Auyeung, B., Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). An exploration of the underdiagnosis of autism in mainland China using screening and diagnostic instruments. Submitted for publication. Cambridge. Sun, X., Allison, C., Matthews, F. E., Sharp, S. J., Auyeung, B., Baron-Cohen, S. (2013). Prevalence of autism in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Autism, 4(1). Wong, V., & Hui, S. (2008). Epidemiological Study of Autism Spectrum Disorder in China. Journal of Child Neurology, 23(1), 67-72. |

|

|

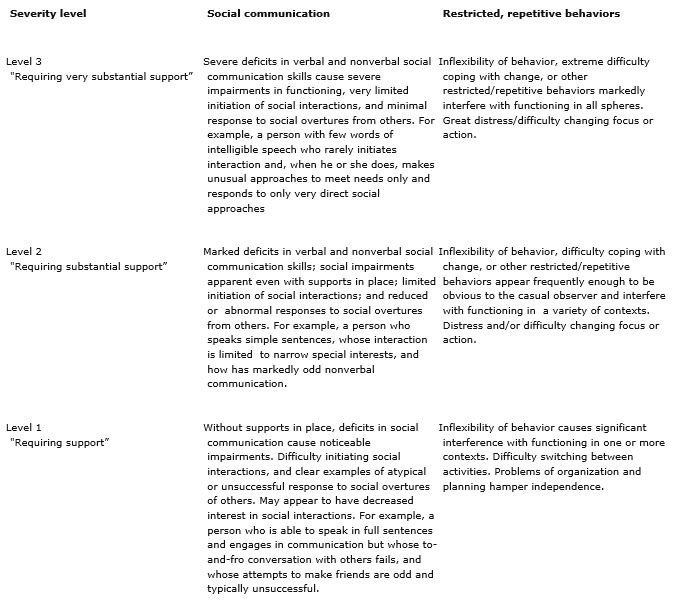

DSM-V: Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnostic Criteria A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive, see text): 1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions. 2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication. 3. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers. Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted repetitive patterns of behavior (see Table 2). B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text): 1. Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases). 2. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns or verbal nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat food every day). 3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g, strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interest). 4. Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement). Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior (see Table 2). C. Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities, or may be masked by learned strategies in later life). D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning. E. These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder frequently co-occur; to make comorbid diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, social communication should be below that expected for general developmental level. Note: Individuals with a well-established DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified should be given the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Individuals who have marked deficits in social communication, but whose symptoms do not otherwise meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder, should be evaluated for social (pragmatic) communication disorder. Specify if: Table 2 Severity levels for autism spectrum disorder

|